The power of paradoxical thinking

by Kristel Van Ael [9 min read]

As we try to solve complex problems, we encounter paradoxes that are seemingly contradictions. We tend to dismiss them as irreconcilable and make a choice for one of the extremes, but by doing so we actually make a big mistake. There will always be discontent/conflict in complexity, and you leave a unique chance unaddressed if you disregard this. In a paradoxical situation the seemingly contradictory factors are both true at the same time and should therefore be addressed together.

My attention was first drawn to paradoxes was draw by a paper written by Kees Dorst and Claus Thorp Hansen in 2011. In their paper Modelling paradoxes in novice and expert design, they compare the way of working between novice (first year students) and expert designers and discovered that the novice designers hardly questioned the given paradoxes. On the other hand, expert designers seem to intuitively understand the power of the paradoxes and use them “to perform an important bridging role between the ‘problem space’ and ‘solution space’.”

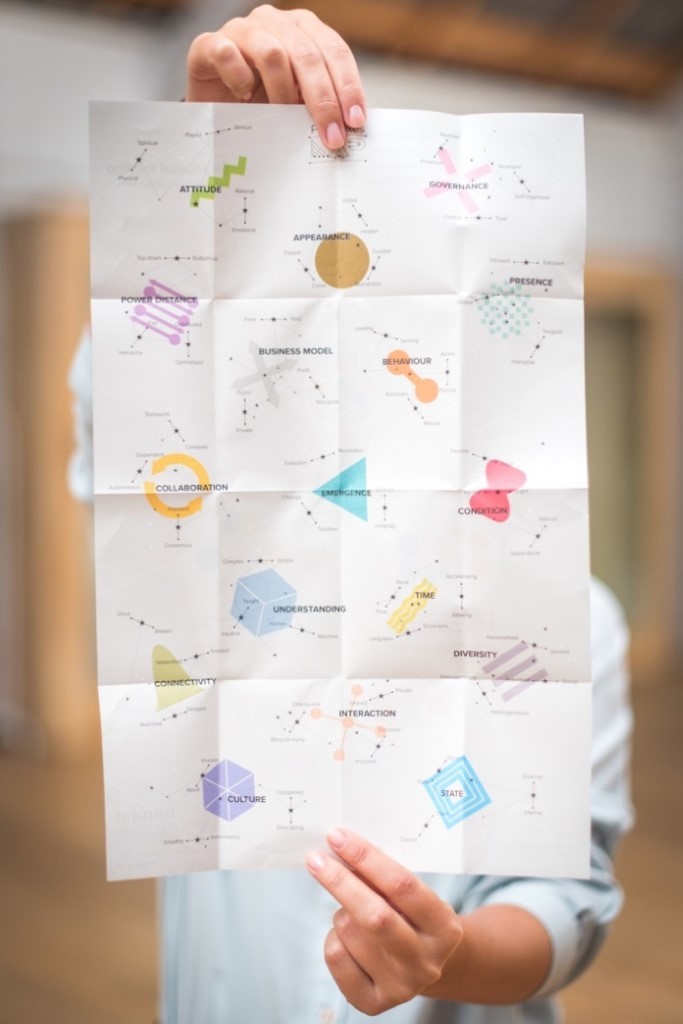

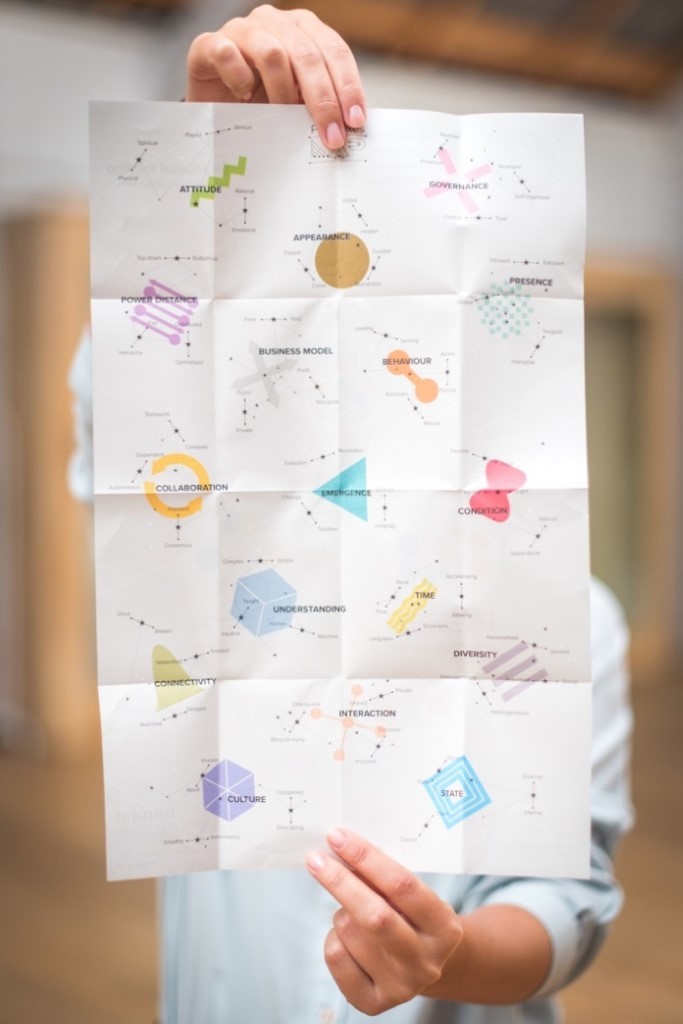

To help ourselves recognize and address the type of contradictions that abound in the projects we work on, we created a set of cards based on the paradoxes identified by philosophers over the centuries. At first it was an in-house tool only, but once we experienced the power of these cards, we decided to create a card deck to be used as a give-away for our clients.

Our website describes the card set as follows: this paradox card set is an ideation tool for consciously bringing together the paradoxical sides of a problem to achieve solutions for the whole. It is about AND thinking instead of OR thinking. It allows you to generate unusual viewpoints and find solutions that suit all in spite of multiple perspectives.

In fact, you can also use the paradox cards in various stages of a project: in the framing phase to hypothetically identify tensions, in the field study phase to let interviewees point out the tensions, and in the conceptual design phase to assess your solutions.

They work because of the underlying energy

Whether we call then paradoxes, polarities, tensions, or even yin and yang, there is an underlying energy that we can leverage. The reason for this is that the poles are interdependent and if you disconnect them, they will start looking for each other, often in a conflicting way.

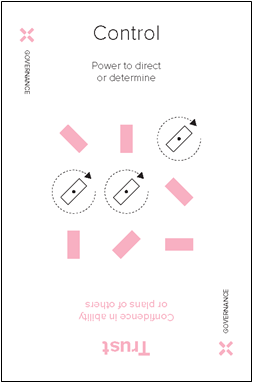

For example, let’s look at the paradox control-trust. In many organisations there is still the idea that you have to control the people working for you. You have to control what they are doing, if they are doing it the right way and what the output is. This is fine but will not work if you are trying to control and also do not trust them, and especially not if they are millennials.

Control only will lead to disengagement and an overall decline of initiative and creativity. Your employees will just do whatever necessary in order to check the box. Trust on the other hand increases intrinsic motivation and stimulates collaboration, especially when facing new challenges. But, of course, this should not lead to chaos and initiatives going in all different directions.

The good news is that control and trust can go hand-in-hand if they are used in a different way. Holacracy, for example, is a method of governance that uses control in an enabling way by establishing self-organising, trusted circles where feedback is appreciated and stimulated. Also, members in a circle tend to trust one another. This trust makes top-down control less necessary and even increases trust in management.

Ways to use the paradoxes

Level one: spotting the tensions in the system

A first usage with the paradoxes is to raise awareness of the tensions in the systems, which could be on different levels: on a societal level, between organisations, within your organisation, when designing products and services or even to resolve conflicts within your own family. Moreover, if the same tension is present on multiple levels it should be dealt with in the different tiers.

Managers, for example, could investigate which dominant factors are at play in their organisations and the degree to which they influence each other. A typical example is long-term vs. short-term vision. Each choice towards an extreme is harmful: only long-term thinking will not bring money on the table and only short-term thinking will make you obsolete in a couple of years. You can also query as to why there is a dominance towards one pole. This could potentially be caused by the pressure of the shareholders, or by a precarious cash situation.

You can also use the paradoxes to assess/benchmark the current offerings in the marketplace. Which of them are only tangible or merely intangible? Are they generic or personalised? Addressing individuals or groups? Can you do better? For example, by making your digital offering more tangible, like a music streaming platform that is also embedded in the physical world and linked to live music festivals.

Level two: creating AND solutions

A common belief is that you have to make a compromise, reconciling the poles somewhere in the middle. The art is to honour both extremes in your solution as much as possible.

Additionally, in complexity there are always multiple polarities influencing each other. A compromise in one pair can lead to a new imbalance in another pair, creating novel conflicts and challenges.

Another advantage of embracing AND solutions is that your solution will be much more future proof by being adaptive to different contexts and shifts in challenges and perspectives. An example of this is the paradox of global vs. local. COVID-19 made it painfully clear to what risks global dependency can lead. But, going back to local production is not the answer. We should find a way in which global and local production are both in place, to foster both scale and local capacities and skills.

Embracing paradoxes also stimulates the ability to create truly innovative products and services. Apple’s iPad, for example, is hugely successful because it solves many contradictions: it’s small but at the same time has a large storage and processing capacity; it is embedded in a closed eco-system but at the same time fostering open innovation; it’s look and feel is both about tradition (slate tablets and icons referring to real-world object) and change, and so on.

Apple also extends this logic to its services: next to an excellent digital platform (intangible) they invest in carefully designed Apple stores, with genius bars to help the customers out in a personalised way (tangible).

Level three: creating reinforcing loops

At first, I used the paradox cards in the ways described above. But then one day I had an ‘ah ha’ moment. I was facilitating a workshop in the health care sector where policy makers and volunteers were meeting for the first time. I first listened to them and soon discovered the tension between the top and bottom approaches. Both approaches were very valuable, and I wondered why they couldn’t find each other.

I started out by drawing the duality on the white board and elucidated a discussion about their differences, but then suddenly I saw that they could actually reinforce each other. I connected them by drawing a reinforcing loop, and we used the remaining time to discuss how this could be done. The volunteer networks could, for example, inform the policy makers of the hurdles that they experience in the field and inspire new common practices by their innovative ways of working. The policy makers could then include this feedback in new guidelines and regulations intended for the field.

Since then, I have always looked at how the paradoxes can connect in a way that they reinforce each other.

Drawings during a workshop for and with EASME and their advisory network.

The drawings above are examples from a project about fostering innovation in Europe. We were looking at how a European network of advisors could better help small and medium enterprises (SMEs) to grow.

On the left, you see the paradox networked vs. isolated. This led to the idea that at first the engagement would be very much one-to-one, between an advisor and a company, but gradually both would become more engaged in a much larger network. A network partner can still advise the client by himself (isolated), but he can also reach other expert colleagues whenever he is not able to find solutions autonomously (networked).

In the middle you have the paradoxes taught vs. intuitive and human vs. machine. These led to ideas on how the virtual space and the physical activities could reinforce each other. For example, a buddy system in whicha partner connects to a virtual space (machine) where he can reach real peers and experts and talk to them (human).

At the right, it’s about top-down vs. bottom up. How can the sharing of knowledge between the advisors be harvested and collected in resources available to all? For example, a partner gets ready-made templates and PowerPoint presentations from the network coordinator (top-down), but he also shares his own materials and presentations with other

colleagues pro-actively (bottom-up). Thus, he reinforces his learning loop and increases the network’s visibility.

The more I use the paradoxes in my work the more I also understand the following quote of Niels Bohr, one of the founders of quantum mechanics: “How wonderful that we have met with a paradox. Now we have some hope of making progress.”

I hope by that this article has sparked your interest in the power of paradoxes. You can buy a copy of the card set on our website or use the list below to experience it for yourself.

Paradox list

Here is the list of paradoxes we include in the cards. They are grouped in 17 subcategories.

Emergence

- Tradition vs. Change

- Instability vs. Balance

- Revolution vs. Evolution

Appearance

- Durable vs. Momentary

- Close vs. Distant

- Visible vs. Hidden

Power distance

- Flat vs. Hierarchy

- Bottom-up vs. Top-down

- Centralised vs. Distributed

Collaboration

- Autonomous vs. Dependent

- Consensus vs. Imposed

- Teamwork vs. Compete

Business model

- Private vs. Public

- Paid vs. Free

- Non-profit vs. Profit

Connectivity

- Isolated vs. Networked

- Delayed vs. Real-time

- Once vs. Always

Understanding

- Complex vs. Simple

- Intuitive vs. Taught

- Machine vs. Human

Diversity

- Group vs. Individual

- Generic vs. Personalised

- Homogeneous vs. Heterogeneous

Behaviour

- Passive vs. Active

- Automatic vs. Manual

- Serving vs. Leading

Governance

- Trust vs. Control

- Self-organised vs. Arranged

- Reactive vs. Proactive

State

- Static vs. Dynamic

- Closed vs. Open

- External vs. Internal

Presence

- Tangible vs. Intangible

- Extrovert vs. Introvert

- Global vs. Local

Interaction

- Many-to-many vs. One-to-one

- Private vs. Shared

- Exclusive vs. Inclusive

Condition

- Stand-alone vs. Add-on

- Rigid vs. Flexible

- Heavy vs. Light

Time

- Flow vs. Stock

- Long-term vs. Short-term

- Slowing vs. Accelerating

Attitude

- Physical vs. Spiritual

- Rational vs. Emotional

- Serious vs. Playful

Culture

- Result vs. Process

- Easy-going vs. Disciplined

- Empathy vs. Performance

The paradox cards are part of the systemic design toolkit.

You can find more context and some of the other tools on www.systemicdesigntoolkit.org.

Posted on October 1, 2020.